|

This article was take from the June, 1953

issues of Automobile Topics, a Floyd Clymer Publication. The article

was written by John D. M. White

As General Motors staged at Dayton, Ohio, the world premiere of its

new Parade of Progress -- "a caravan of science", designed

to explain the meaning of research and better engineering to the

man-in-the-street, a GM executive predicted at America's opportunities

for further progress are greater now than ever before.

The later statement keynoted the remarks of Paul

Garrett, vice-president in charge of the GM public relations staff,

who 'emceed' on May 12 a noon press-radio-TV preview of the

big exhibition which has begun a cost-to-coast tour.

Previously, the non-commercial Parade had completed

'shake-down' shows at Frankfort and at Lexington, Kentucky,

initiating its tour to the accompaniment of what John E. Johnson,

consultant to the Parade, termed "frog-drowning" rains.

These persistent downpours made the young crews of lecturers and

drivers red-eyed with "round-the-clock" experience in tent

raising and de-bugging of exhibits, but apparently did not completely

dampen the ardor of the curious, for a gratifying attendance was

attracted.

Charles F. Kettering, of Dayton, famed inventory

and 'father' of the original Parade of Progress in 1936,

spoke on some of the scientific advances expected in the near future.

Now a GM director and research consultant, Mr. Kettering formerly

headed the company's research laboratories.

President Harlow H. Cutice could not be present,

due to other engagement and wired his greetings, but a battery of

other GM executives attended, including vice-presidents Charles I.

McCuen, general manager of the Research Laboratories Division, and

Charles A. Chayne, in charge of the engineering staff.

The evening was marked by an invitational civic

preview, held in the caravan's silver-colored Aerodome 'big

top', a special tent seating 1,250 people. Several hundred

educators, scientists, civic and industrial leaders and their families

attended.

Mr. Garrett, speaking at the preview in the

Aerodome, asserted: "Few people stop to realize just how dramatic

our progress has been. For example, it is difficult now to appreciate

what has happened to highway transportation within the memory of men

still living.

"The first horseless carriage made its debut

in this country not so very long ago, as we look back. Living in a

small town out west, I was 18 before I saw my first automobile. Yet

today, there are more than 50 million of them in America alone.

"And what this revolution has meant in terms

of jobs is even more amazing. Two generations ago highway

transportation was relatively unimportant as a source of employment in

this country. Today, one out of every seven workers owes his

livelihood, directly or indirectly, to the vehicles that roll on

highways.

"Through the Parade of Progress we hope to

bring home to people the fact of such change, of such increased

opportunities for jobs.

Outlining the aims of the Parade of Progress,

Garrett said:

"We think it would be worth a great deal to

all of us if there were a better understanding of why America has come

so far in the world and within so short a time.

"We also want our audiences to understand how

this progress has been achieved -- in other words, the role played by

science, by research, and by engineering -- backed up by an economic

and political system that over the long run has given people the

freedom to think, create and compete and has rewarded those who make

better products and help people live better."

Mankind in the old days was limited by the number

of men and animals that could be put to work," he pointed out, adding:

"Today, the only limit is the amount of power

that can be coaxed from machines. And the power potentialities of the

future are virtually unlimited.

"That is another point we want our audiences

to get: not only is the world definitely not finished, but opportunities

for further progress are greater now than ever before."

"To set a boy to dreaming," is another

major objective of the Parade, Garrett concluded:

"Because technological progress has been so

rapid over the past few years, with new discoveries opening up so many

new avenues of research, the available supply of young scientists and

engineers falls far short of the demand.

"If in the near future we don't get enough new

scientists and engineers to enable the demand to be met, our rate of

progress will lag. And so the Parade seeks to interest youth in making

a career in the technical progressions."

The initial Parade played before about 12-1/2

million people in 251 cities from 1936 to 1941, and was disbanded

after Pearl Harbor in 1941. The new Parade, now starting out, has been

rebuilt to show some of the outstanding advances in science in recent

years.

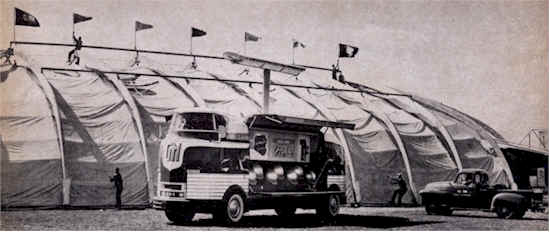

The Parade, operated by 55 young men, includes a 40-minute stage show

of science, presented six to eight times daily in the Aerodome. In

addition, the caravan features 26 major exhibits, displayed in a dozen

Futurliners. These are 33-foot long vans with 16-foot sides that open

to reveal the exhibits or to form small lecture stages.

Ten tractor-trailers, four other trucks, and 18 new

passenger cars complete the Parade, which moves from city to city, in

a three-mile procession at abut 35 mph. The vehicles maintain a separation

of 300 feet. The men of the Parade drive all the vehicles and give the

lectures, put on the science demonstration, and conduct the stage

show. Mechanics and a service trucks accompany the Parade.

In the stage show and the exhibits, which are free

to the public, the Parade dramatizes progress in such fields as

transportation, aviation, electronic, chemistry and power. Lecturers

operate some of the exhibits. Others are animated models with

synchronized sound. Several exhibits can be operated by visitors.

Preview guests at the tent show saw such scientific

advances as:

- A model jet engine, that operates with an

ear-splitting roar.

- A small microwave tower setup, such as used in

radar and TV, that "broadcasts" across the stage.

- A glass bottle so tough on the outside that a

lecturer uses it to hammer a spike through a plank; yet the bottle is

so weak on the inside that a pea-sized abrasive, dropped into a

bottle, smashes it to bits.

In brief, the Parade's purpose is to show basis

principles of science and what they mean to people -- at home and at

work.

GM spokesmen explained that in capsule form the

Parade displays products of modern engineering, research and science

that do not bear a General Motors trademark. Rather, they represent

engineering in a broad sense. They illustrate basic science principles

that both engineers and researchers deal with in their daily lives.

Vice-president McCuen has pointed out that, this

"newness" of these products lies in the application of the

principles, declaring: "It is virtually axiomatic that there is

nothing new in engineering.

"Almost every modern development can be traced

back either to some crude apparatus of an imaginative inventory or to

the recorded speculations of some scientists, philosophers or

observers -- men ahead of their times," he said.

"Other developments have sprung from

accidental discoveries of investigators searching for something far

removed from the objective they attempted to attain. But they

were keen enough to capitalize immediately on their un-expected

discoveries."

Pointing out that one of the featured exhibits is a

small motor -- a sun motor -- which converts into electricity enough

power from the sunlight to spin a light balsa wood wheel, McCuen said:

"It generates enough power actually to do

little more than illustrate a principle, the principle that sunlight

contains energy. Nature knew this before the beginning of time. All

our fuel in the form of coal, oil and natural gas is the result of

nature's method of storing energy in plants.

"Perhaps some day, either by accident or by

continuous, unrelenting research, an alert engineer or scientist will

discover the way to convert solar energy efficiently, directly from

the sun so we may use sun power for everyday utility purposes.

"When a commercially efficient method is

developed," he said, "it will have more far reaching effects

on civilization than any engineering development which has been made

up to this time.

The executive explained that the principle of jet

propulsion, dramatized with an Allison turbojet cutaway exhibit, harks

back to 130 B.C. That was when Hero of Alexandria, Egypt, built a

device to move symbolic figures on an altar.

Centuries later came the 'smoke jack,' a

windmill device in a chimney. Hot gases rising from the chimney base

or hearth caused it to rotate. The rotational power was used for such

tasks as turning the spit over a fire.

The crude predecessor of the gas turbine engine or

turbojet is the 'smoke jack.' The draft effect of the chimney

is reproached by an air compressor, the chimney hearth by a burner or

combustion chamber and the 'smoke jack' by a turbine wheel.

From Mr. McCuen and his aides at the laboratories

come other interesting examples of the growth of science in our modern

living.

In discussion about automobiles these days, the

term 'high compression' is part of the language. More than

65 years ago an Englishman, Dugald Clerk, observed that by raising

compression ratios it would be possible to raise efficiency of

internal combustion engines.

Also, he recognized 'knock' or 'pre-ignition,' as he called it, would be a limiting factor,

a ceiling to further increases in compression ratio. At that time,

however, he could not recognize the role that modern antiknock fuels

would play in permitting engineers to raise automotive engine

compression ratios.

The GM executive reminds us that today's automotive

engines with their increasing compression ratios are providing the

validity of Clerk's theories. The elementary principle of increasing

compression ratios for greater efficiency (more miles per gallon) is

relatively ancient, but current application of it is relatively new.

It wasn't applied in Clerk's time to the extent it

is today because over the past few decades both engine designers and

fuel chemists had to learn more about combustion, the behavior of

various fuels and engines.

"The designer, to cope with high cylinder

pressures, had to learn how to develop 'stiffness' in the structure of

an engine," Mr. McCuen said. "In his early experiments he

found that as compression rose, engine roughness increased. A rough

engine never attracted passenger automobile customers."

"Meanwhile", he explained, "the fuel

chemist had to examine, step by step, the molecular structure of

fuels. They learned that fuels with long, stringy molecules showed a

tendency to knock, to limit the engines power output. When molecules

were closely and compactly arranged, the fuels burned smoothly. this

meant more efficient use of fuels in high compression engines."

This leads to the interesting conjecture that no doubt, unwittingly, a

tribe of ancient Polynesians fathered the Diesel engine. To start

their fires they used a bamboo cylinder, a plunger and dry moss. By

thrusting the plunger into the cylinder or tube, they generated enough

heat from air compression to ignite the dry moss on the end of the

plunger.

This Polynesian fire-maker utilized the principle

of compression ignition. This same principle today is used by the

Diesel engine which has the highest efficiency of any internal

combustion engine in commercial service. This is another instance of a

relatively new application of an old principle.

And Mr. Chayne sums up the answer to the query

"What does 'better engineering' mean to the average person?"

in this fashion:

"Better engineering means better living. The

exhibits in the Parade of Progress provide many specific answers to

the question. They show several ways in which engineering helps to

improve our living standards.

"One of my favorite examples naturally

concerns automobile engines. With 53 million cars in this country

today, engines are important to almost everybody.

"A good automobile engine of, say, 40 years

ago, was about five feet long and developed around 60 horsepower. It

was in a car listing at over $4,500. Yet all you got out of this

engine was six or seven miles per gallon of gas.

"Today's engine, in a comparable model, is

less than half as bulky, but it turns up nearly three times as much

horsepower. Moreover, it gives from 15 to 20 miles per gallon. And

despite inflation, the car's price -- including the new engine and

hundreds of other improvements -- is only about half as much as in

those early days.

"The reason -- better engineering --

coupled with extensive research -- both in the automobile industry and

the petroleum industry.

"For the man, or woman, behind the wheel, the

significant aspect to this engineering progress is that today's car

gives more comfort, performance, and pleasure for far less

money."

Mr. Chayne has been with General Motors for 23

years. Before being appointed to his present position, he was Buick's

chief engineer for 14 years. He comes from Harrisburg, PA and received

his engineering degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Commenting about the Parade of Progress, Mr. Chayne

noted that it presents the story behind many outstanding engineering

achievements.

"My hobby", he said, "is antique

automobiles, but my business is to make today's models obsolete

tomorrow -- through constant improvements.

"The old cars I collect are fascinating, for

they constantly remind me that there is always an opportunity to build

better ones.

"At the same time, in addition to designing

better cars, we continually seek to improve our manufacturing methods.

In these days we try to offer more value to the public each year.

"That, essentially, is the philosophy of

engineering -- do the job in a better way and make a better

product."

Post war years, Mr. Chayne pointed out, have seen

such automotive, engineering and production milestone as these:

1. New types of automotive transmissions -- to do

away with hand-shifting.

2. High compression engines -- to increase mileage

and performance, while giving smoother operation.

3. Increased use of power equipment -- to make

steering easier, braking safer and quicker.

4. Air-conditioning, better heating and ventilating

-- for greater comfort and safety in all types of weather.

"One of the exhibits in the Parade," Mr.

Chayne noted, "provides another illustration of what research and

engineering can do for the entire nation.

"The exhibit is titled 'High Compression --

Power and Economy." Here you can see how progress in fuels

already has saved us a third of our fuel resources and how science and

engineering can save us another third.

"For example, raising the compression ratios

in our modern automobiles to 12 to 1 would save a million tank cars of

gasoline a year. It would take 144 hours for those million tank cars

to pass one spot if they were traveling at 60 miles per hour.

That's a lot of hours, a lot of gasoline, and a lot

of economy -- but it can be achieved. We're headed that way now."

Following a trend established earlier this

year by the Chrysler Company, Kaiser Motors Corp., announced

reductions on the delivery prices of the Henry J Corsair and Corsair

DeLuxe, of $100 and $125 respectively.

Roy Abernethy, vice-president and general manager

of the Kaiser-Frazer Sales Corporation, announced that reductions will

take place immediately. This will make the Corsair $1,399.00, F.O.B.

Detroit.

|